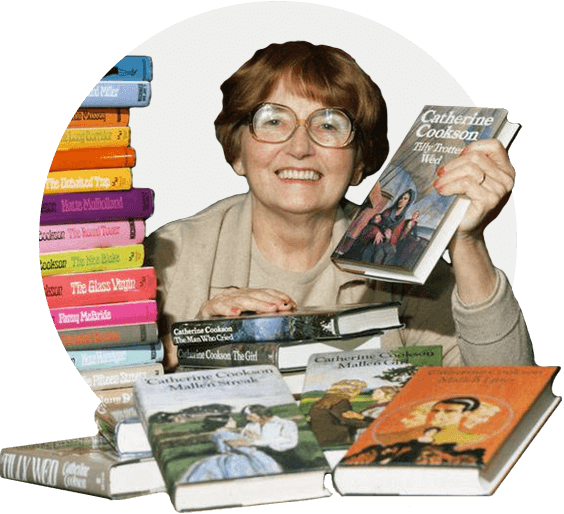

Dame Catherine Ann Cookson, DBE (née McMullen; 27 June 1906 – 11 June 1998) was a British author. She is in the top 20 of most widely read British novelists with sales topping 100 million, while retaining a relatively low profile in the world of celebrity writers. Her books were inspired by her deprived youth in South Tyneside, North East England, the setting for her novels. With more than 103 titles written in her own name or two other pen-names (see Bibliography below), she is one of the most prolific British novelists.

Early Life

Cookson (registered as Catherine Ann Davies) was born at 5 Leam Lane in Tyne Dock, South Shields, County Durham and known as “Kate” as a child. She moved to East Jarrow, County Durham which would become the setting for one of her best-known novels, The Fifteen Streets. The illegitimate child of an alcoholic named Kate Fawcett, she grew up thinking her unmarried mother was her sister, as she was brought up by her grandparents, Rose and John McMullen. Biographer Kathleen Jones tracked down her father, whose name was Alexander Davies, a bigamist and gambler from Lanarkshire.

School and Early Employment

She left school at 14 and, after a period of domestic service, took a laundry job at Harton Workhouse in South Shields. In 1929, she moved south to manage the laundry at Hastings Workhouse, saving every penny to buy a large Victorian house, and then taking in lodgers to supplement her income.

Marriage to Tom Cookson

In June 1940, at the age of 34, she married Tom Cookson, a teacher at Hastings Grammar School. After experiencing four miscarriages[6] late in pregnancy, it was discovered she was suffering from a rare vascular disease, telangiectasia, which causes bleeding from the nose, fingers and stomach and results in anemia. A mental breakdown followed the miscarriages, from which it took her a decade to recover.

Writing Career

She took up writing as a form of therapy to tackle her depression, and joined Hastings Writers’ Group. Her first novel, Kate Hannigan, was published in 1950. Though it was labelled a romance, she expressed discontent with the stereotype. Her books were, she said, historical novels about people and conditions she knew. Cookson had little connection with the London literary circus. She was always more interested in practising the art of writing. Her research could be uncomfortable—going down a mine, for instance, because her heroine came from a mining area. Having in her youth wanted to write about ‘above stairs’ in grand houses, she later and successfully concentrated on people ground down by circumstances, taking care to know them well.

Over 123 million copies sold

Cookson wrote almost 100 books, which sold more than 123 million copies, her novels being translated into at least 20 languages. She also wrote books under the pseudonyms Catherine Marchant and a name derived from her childhood name, Katie McMullen. She remained the most borrowed author from public libraries in the UK for 17 years, up until four years after her death, losing the top spot to Jacqueline Wilson only in 2002.

Books in Film, Television and Stage

Many of Cookson’s novels have been adapted for film, radio, and the stage. The first film adaptation of her work was Jacqueline (1956), directed by Roy Ward Baker, based on her book A Grand Man. It was followed by Rooney (1958), directed by George Pollock, based on her book Rooney. Both starred John Gregson. For commercial reasons, the action of both films was transferred from South Shields to Ireland.

In 1983 Katie Mulholland was adapted into a stage musical by composer Eric Boswell and writer-director Ken Hill. Cookson attended the première.

Books in Television

It was on television, however, that she had her greatest media success, with a series of dramas that appeared over the course of a decade on ITV and achieved huge ratings. Eighteen books were adapted for television between 1990 and 2001. They were all produced by Ray Marshall from Festival Film & TV who was given permission by Cookson in 1988 to bring her works to the screen. The first film to be made, The Fifteen Streets starring Sean Bean and Owen Teale, was nominated for an Emmy award in 1990. The second production, The Black Velvet Gown, won an International Emmy for Best Drama in 1991. The mini series regularly attracted audiences over 10 million and are still showing in the UK on Drama and the Yesterday Channel.

.png)

Philanthropy

In 1985, she pledged more than £800,000 to the University of Newcastle. In gratitude, the university set up a lectureship in hematology. Some £40,000 was given to provide a laser to help treat bleeding disorders and £50,000 went to create a new post in ear, nose and throat studies, with particular reference to the detection of deafness in children. She had already given £20,000 towards the university’s Hatton Gallery and £32,000 to its library. In recognition of this generosity, a building in the university medical faculty has been named after her.

Catherine Cookson Charitable Trust

The CCCT continues to support many worthy causes within the UK.

Honours

She was created an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1985 and was elevated to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1993.

Cookson received the Freedom of the Borough of South Tyneside, and an honorary degree from the University of Newcastle. The Variety Club of Great Britain named her Writer of the Year, and she was voted Personality of the North East.

Later Life and Death

In later life, Cookson and her husband Tom returned to the North East and settled first in Haldane Terrace, Jesmond. They then moved to Corbridge, a market town near Newcastle, and later to Langley, Northumberland, a small village nearby.

As her health declined, they moved for a final time to the Jesmond area of Newcastle upon Tyne in 1989 to be nearer to medical facilities. For the last few years of her life, she was bed-ridden and she gave her final TV interview to North East Tonight, the regional ITV Tyne Tees news programme, from her sickbed. It was conducted by Mike Neville.

Catherine's Death

Catherine Cookson died at the age of 91, sixteen days before her 92nd birthday, at her home in Newcastle. Her novels, many written from her sickbed, continued to be published posthumously until 2002. Tom died just 17 days later, on 28 June 1998. He had been hospitalised for a week and the cause of his death was not announced. He was 86 years old.